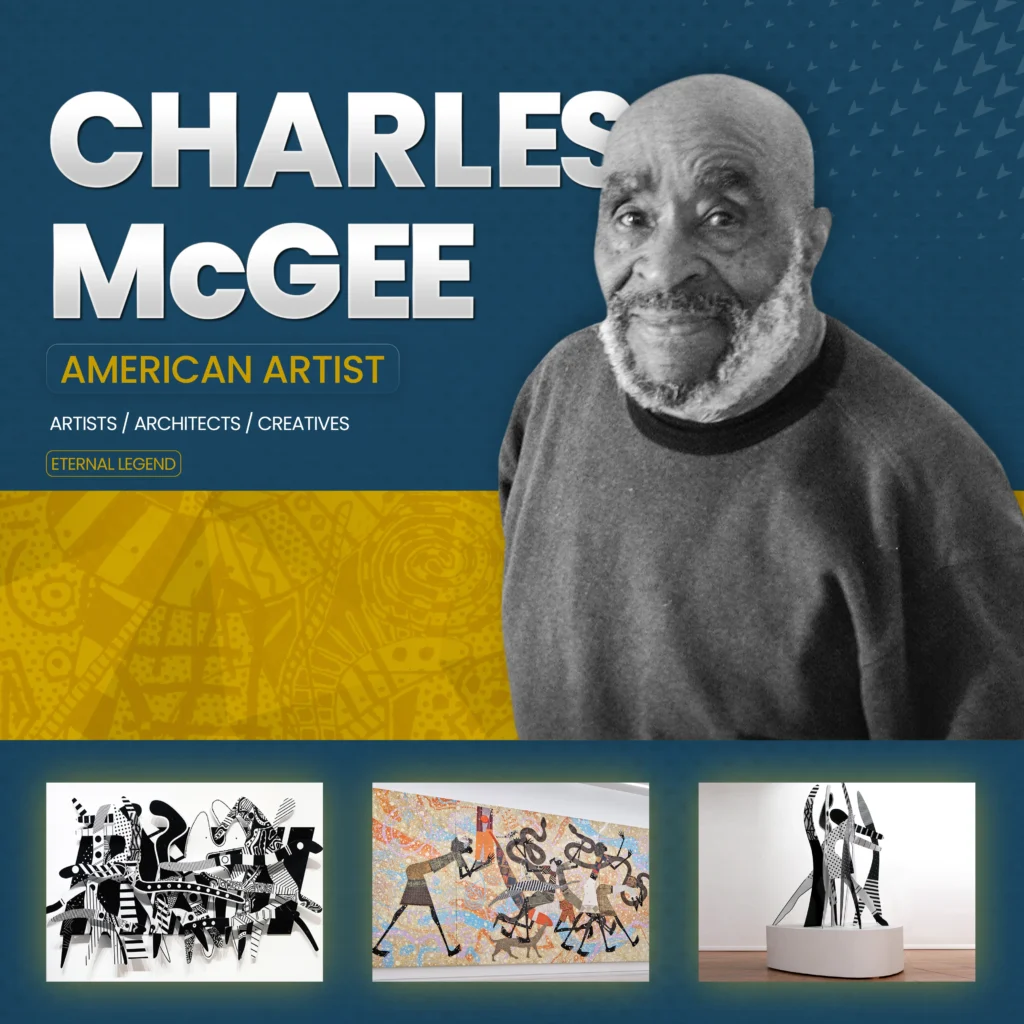

McGee’s style was unmistakable:

Bold lines.

Interlocking forms.

Urban Hieroglyphic merged with African diasporic geometry.

His work was layered and abstract – like dancing puzzle pieces.

He thought all things were interconnected: nature, jazz, struggle, and celebration – all in one composition.

He once said:

He once said, “The universal language is art. And it speaks across cultures and across time.”

In his hands, that became Detroit’s dialect.

McGee produced work until he was 96 – nearly 80 years of unbroken creativity.

He painted, collaged, and sculpted during Detroit’s turbulent 1960s and 70s, which saw civil rights marches, white flight, and the ’67 uprising.

His Contemporary Art Institute of Detroit was founded in 1978 to showcase his work and challenge the gallery system, but his public art really exploded around the city in the 2000s:

McGee’s piece, “Unity” (2017), is on the side of the Charles H. Wright Museum, celebrating connection through difference.

“Still Searching” (2016) is in The Detroit Institute of Arts.

And his mixed-media pieces are in the Whitney, Detroit Institute of Arts, Smithsonian, and MoMA permanent collections.

That said, his art was not what made McGee most remarkable.

It was his humility.

He thought artists and their work must be near people – never above them.

In that way, McGee was a guardian of artistic lineage.

Informally, he taught thousands through CCS and various projects, panels, and random encounters, and his work is cited by various artists including Tyree Guyton, Tiff Massey, and Sydney G. James.

The man never spoke.

He listened.

He encouraged.

He wanted Detroit’s next wave to go beyond what just he had done, and young artists who visited his studio found a man still experimenting – sculpting wire into thought, painting with childlike curiosity, refusing to become cynical.

Please check your email for your login details.

Please check your email for your login details.