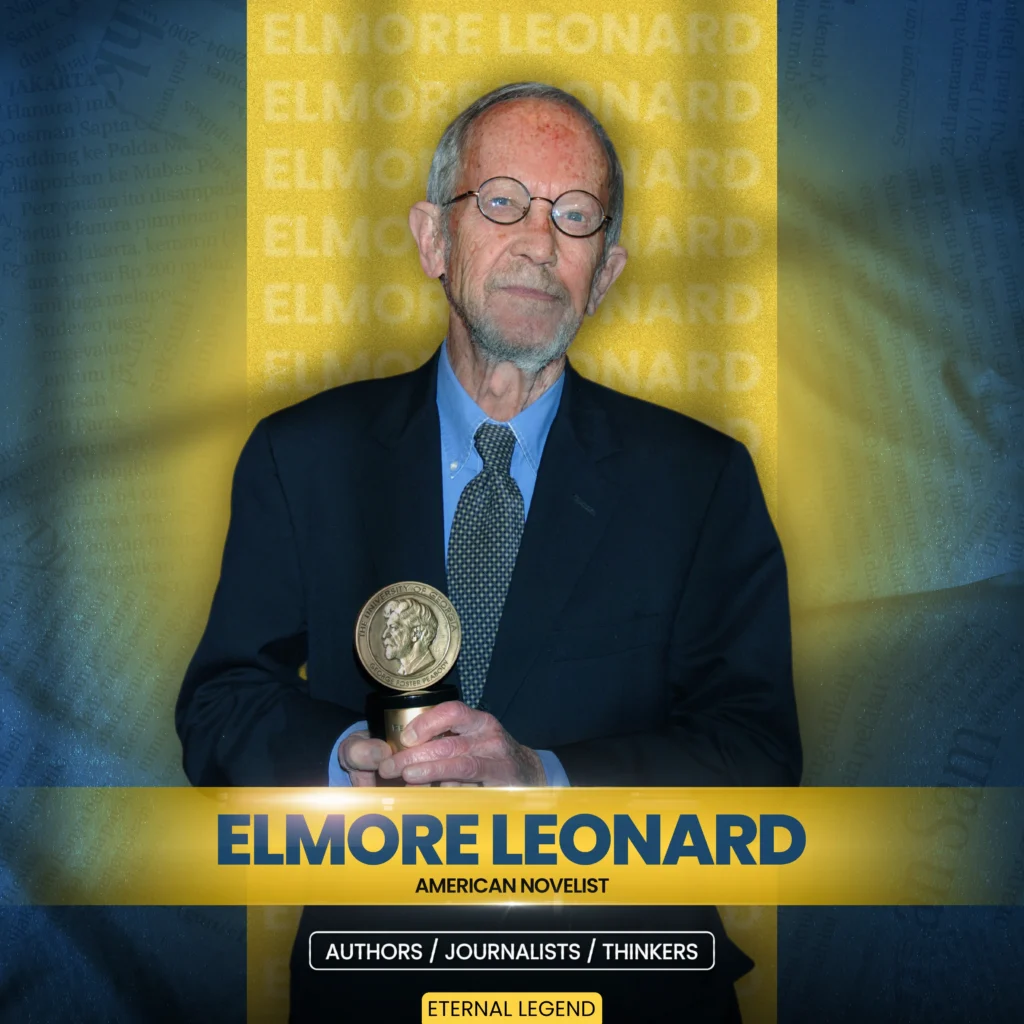

Leonard started writing as a Western novelist in the 1950s, which saw him penning stories like “Hombre” and “3:10 to Yuma” – the latter of which was made into a Hollywood film not once but twice.

It was only when the Wild West dried up that Leonard turned his attention east toward the gritty streets of Detroit.

It was the 1970s, and the city was cracking under the weight of police corruption, white flight, heroin, auto layoffs, and arson.

Leonard’s reaction?

He refused to paint the city as noble.

Instead, he gave us hustlers, ex-cons, hitmen, and half-smart crooks who thought they had it all figured out (spoiler alert: they never did) as well as dialogue that hit like a jazz riff.

Leonard never described characters.

He let them speak for themselves…and what came out were voices you’d swear you had heard on 7 Mile, Cass Avenue, or in the back of a bail bondsman’s Buick.

His writing rules became legendary:

Leave out that bit that readers skip over.

And when it sounds like writing, rewrite it.

He had tight prose. His wit was dry. And he told stories that moved like a getaway car with a half-flat tire – fast, dangerous, unpredictable.

In Leonard’s work, Detroit became a character in and of itself, not just a location.

Books like City Primeval, Freaky Deaky, Swag, and 52 Pickup are love letters to a city that had been mugged, flipped, and left for dead – yet continued to talk back.

Not only that, but the class tension between Grosse Pointe and 8 Mile were also perfectly captured by Leonard, with Detroit’s suburban sprawl making many of his getaway scenes longer, quieter, and punctuated by pool halls and pawn shops.

Please check your email for your login details.

Please check your email for your login details.