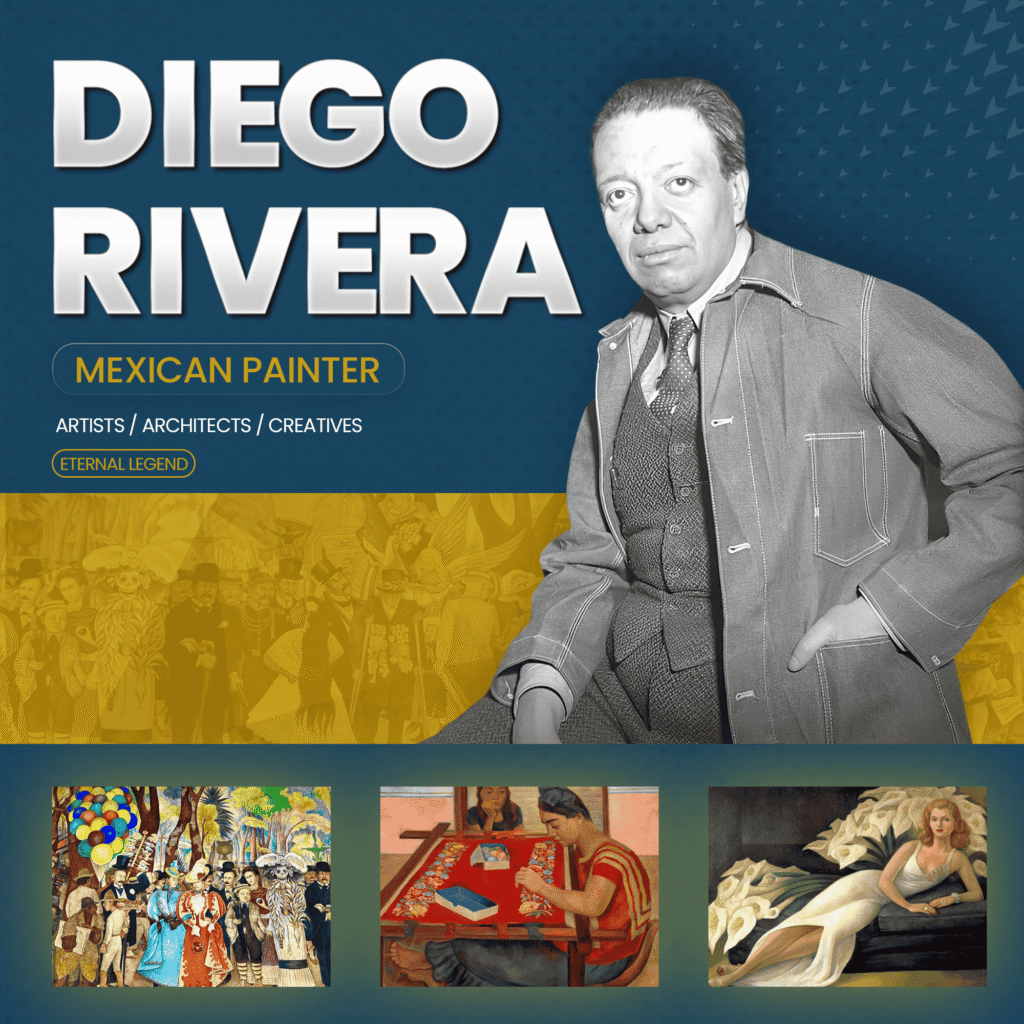

Diego Rivera did not just paint walls.

Rivera did not just paint walls.

He crafted revolutions in concrete.

Rivera arrived in Detroit in April 1932 to find the city struggling under the weight of the Great Depression.

It was a time when unemployment was high, factories were closed, and stomachs were empty.

Black smoke hung from the skyline, and the mood was somber and gray.

And yet, out of that bleak canvas stepped Rivera: barrel-chested, defiant, brilliant.

He brought color.

Meaning.

Fire.

Months later, he would transform the Detroit Institute of Arts into a temple for the working class – and scandalize the city’s elite at the very same time.

Please check your email for your login details.

Please check your email for your login details.